Thanks for your contribution

The information you provide helps us to continue to develop and improve Amelia Virtual Care. Remember that you can contribute your ideas in our feature request.

The information you provide helps us to continue to develop and improve Amelia Virtual Care. Remember that you can contribute your ideas in our feature request.

Psious heatmaps are graphic representations in which a color code is used to highlight the most visited areas within a virtual scene. These representations are based on thermography.

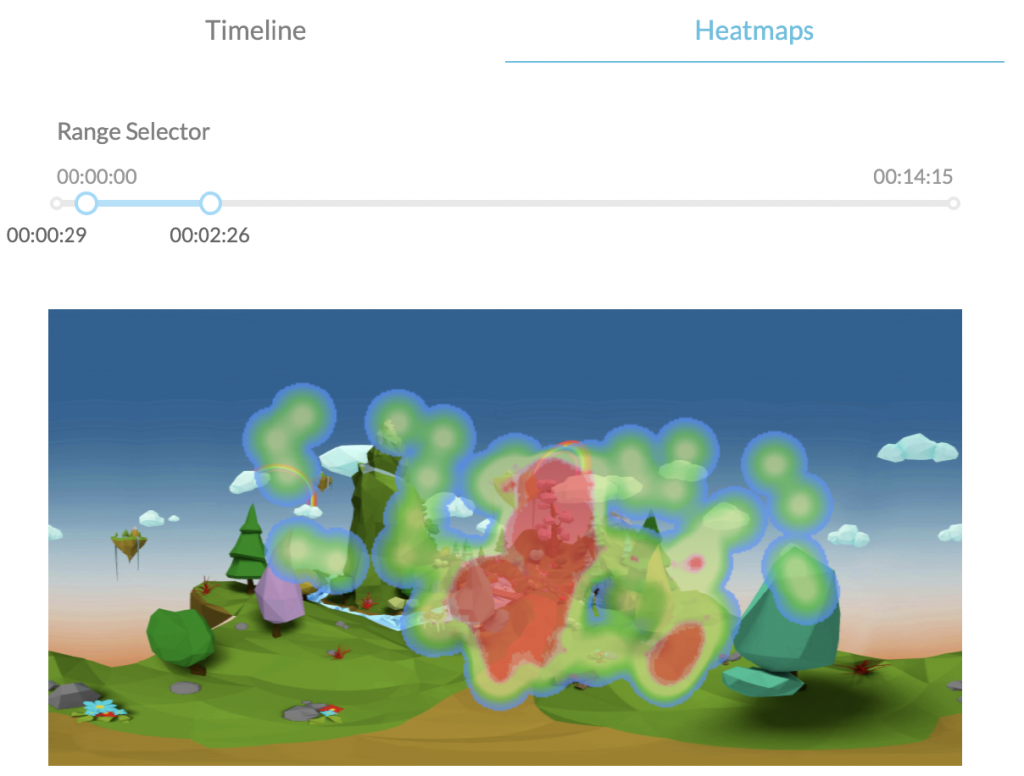

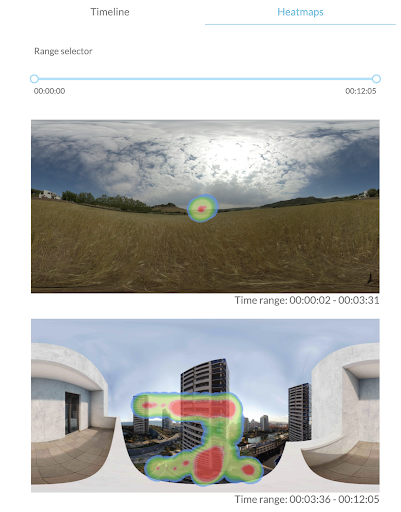

Psious Heatmaps (PHMs) are meant to portray the orientation of the patient’s head inside virtual reality scenes. Using this method provides information on the user’s behavior while detecting which items inside of the scene are those most observed by the user. In order to be visually interpreted, PHMs require, on the one hand, the scene context and, on the other, the events activated within that scene. To collect that information and represent it in a way that is simple and accessible, Psious.pro stores the direction of the head every 0.3 seconds and uses that information to create a graphic portrayal which is superimposed over an equirectangular image of the virtual scene, such as an airplane during takeoff while seated by the window during good weather. One must bear in mind that the data from a PHM are directly related with time. In other words, the final representation of a heatmap provides us with knowledge about how the patient behaved during a certain range of time. This time range may consist of an entire session or part of one. To create the representation of the head’s orientation and time employed by the patient, a color gradient is used (green-red) in which the area represents the places where the patient looks and the color represents the time which the user spent looking in that direction . Warm colors (reds) represent the areas looked at for the longest time, while cool colors (greens-blues) highlight the areas with which the patient has interacted less. Last of all, the areas which are not colored indicate that there was no interaction with those spaces within the scene. Psious.pro creates one PHM for each scene, or in other words, each time there is a change in the virtual environment… In any one session, there may be just one PHM or several. Before beginning the therapeutic scene, a PHM is displayed over the waiting space (a wheat field). This may be used as the base line or for adaptation.

If the virtual environment exists in a changing space, the PHM shows different images based on the spaces in which the session occurs within the virtual environment.

Ultimately, the general purpose of PHMs is to help discriminate what our patient’s orientational behavior has been like while using a virtual environment for a specific period of time. Moreover, we can collect overall information on the patient’s interaction within the environment when compared with the total duration of a scene or to adjust it for a specific time period.

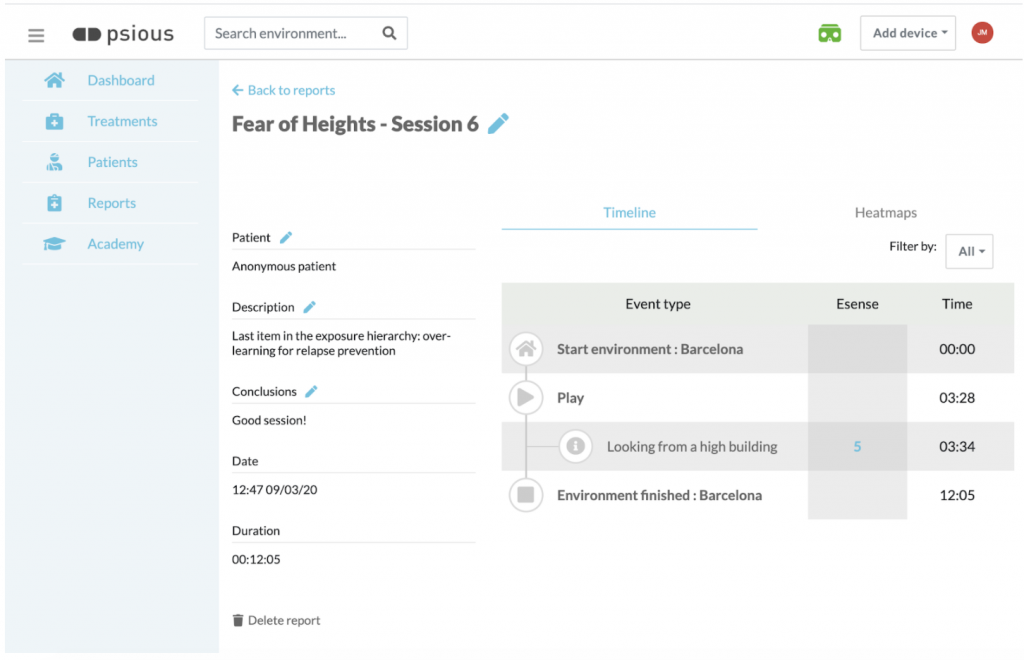

The heatmaps are found within the sessions reports. Once the session has ended, the session report is displayed (Fig. 4). This report shows, in addition to the general information (GI) on your patient and these session data (description, conclusions, date and duration), a graph with the physiological measurement (s) and subjective anxiety units (SAUs) recorded during the session , and the timeline (TL), which sequentially displays everything that took place during the session (activation of environments, setup variables, launch of events …). You also have the section Heatmaps (PHMs), which is to the right of the TL, by selecting PHM (Fig. 5).

Remember that you can also access the session reports at any time by going into the Reports section in the side menu on Psious.pro

Before beginning to discuss the clinical applications of PHMs, it is important to define a few concepts related to behavior. We shall now briefly define them:

The orientation reaction, also referred to as the orientation reflex, is the body’s immediate response to a change in its environment, when the change is not sudden enough to produce the startle reflex[1]. This occurs when someone’s attention is attracted by an intense, significant stimulus from a biographic perspective, causing the head and eyes to turn towards the stimulus, changes in respiratory rate, heartbeat deceleration, dilation of the blood vessels in the head, and unsynching or inhibition of the electroencephalogram alpha waves. The purpose of the orientation reaction is to facilitate the perception of stimuli. The orientation reaction is easy to habituate through repetition of a stimulus.

Example: Once our patient is located within the virtual environment and certain innovative stimuli appear, whether due to the very dynamics of the environment or because we have set off a specific event to modify it, the orientation reaction will either appear or not arise. Whether or not it arises, the delay time between the occurrence of the stimulus and the patient’s response will be relevant variables in evaluating and monitoring therapeutic change throughout the intervention.

[1] Startle reflex: The startle reflex (SR) is a rapid, involuntary reflex contraction of the muscles in face and limbs which follows a rostral-causal progression pattern and is caused by sudden, intense stimuli involved any of the senses: acoustic, visual, olfactory, somatosensory or vestibular (Landis and Hunt, 1939). The SR pattern consists of eyelid closure and contraction of the face, neck and skeletal muscles, as well as blockage of the conduits already initiated, along with an acceleration of heart rate. The usual response consists of a brief flexion which is more notable in the upper half of the body (Valls-Solé, 2004).

According to Tolman (1932), purposive behavior is that which aims to achieve certain goals. It is persistent and displays selectiveness in terms of achieving that goal. This author suggested several types of causes to explain purposive behavior: primary, secondary and tertiary motives. Among the primary motives (innate) are the search for food, water and sex, the elimination of waste, the avoidance of pain, rest, aggression, reducing curiosity and the need for contact. The secondary (innate) motives include affiliation, dominance, submission and dependency. The tertiary (acquired) include those which involve the achievement of cultural goals.

Example: Depending on the therapeutic objective established (evaluation or intervention, reducing anxiety in the presence of a conditioned stimulus, selected or sustained attention, etc.), we can obtain measurements about a patient’s purposive behavior in the virtual environment, using the PHMs. PHMs provide us with information which allows us to evaluate what causes the patient’s behavior within the virtual environment (avoiding stimuli from the virtual environment to manage discomfort, exploring the new environment, earning points, paying sustained attention to specific stimuli, etc.).

Exploratory behavior consists of activity aimed at gathering information about the unknown. This may be caused by new stimuli (Barnett and Cowan, 1976) and constitutes an important aspect of purposive behavior (Cathomas et al., 2015). Exploration of new things and places has been related with motivation through the conceptualization of exploratory behavior in animals. On the one hand, as an innate “need” to search for sensory change (Hughes, 1997) and, on the other, with the neurobiological substrates common to novelty and reward (Bunzeck et al., 2012; Düzel et al., 2010 ; Krebs et al., 2009). Exploratory behavior may be influenced by development time (Sidney W. Bijou, 1998), emotional states (Lang et al., 1990 and 1997) and pathology (e.g., Siddiqui, I. et al., 2017).

Example: PHMs allow us to observe whether, once within the virtual environment, the user displays or does not display exploratory behavior in the environment, whether he or she does so upon activating the environment, or whether it begins once the patient’s emotional state has changed.

Appetitive responses, aimed at consummation, sexual or breeding behaviors, are those which take place at the beginning of a natural behavioral sequence and are meant to put the body into contact with a triggering stimulus.

Defensive responses means behaviors for protection. In behaviorist psychology, avoidance behaviors form part of, along with behaviors for escape, a basic procedure within instrumental conditioning. Some theoretical models also include the blockage / freezing response among the defensive reflexes. This type of behavior occurs both as an innate response to novel stimuli and as a conditioned response to learned stimuli. In the escape or flight response, the individual uses some form of action to put a stop to an unpleasant or painful stimulus (Kim BW, et al., 2010). Both behaviors may be viewed as motivated forms of conduct aimed at avoiding uncertainty (removing discomfort due to a lack of information, eliminating emotional discomfort, pain). As systems of action, the appetitive and defensive responses work in a reciprocally inhibitory manner.

Third generation therapies, especially Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), have used the behaviorist terms of avoidance and escape, including cognitive and conceptual elements within the traditional concept: experiential avoidance (Hayes et al., 1996).

Example: Depending on the therapeutic goals established (evaluation or intervention), one may observe how the patient establishes contact with a series of stimuli (warm colors) and avoid others (cool colors and uncolored areas in the representation of the environment). Likewise, one may observe, for instance, whether a frightened patient becomes still, does not explore and avoids certain stimuli in the environment.

To state it in a very basic way, we can define attention as the cognitive and behavioral process of perceptive and selective focusing on a discrete aspect of information, whether this is voluntary or involuntary, whereas other stimulating factors are ignored Anderson, John R. ( 2004). From the perspective of psychology, attention is not one single concept, but rather is the name attributed to a variety of phenomena. Traditionally, it has been regarded in two different, though related ways. On the one hand, attention viewed as a quality of perception refers to the role which attention plays as a filter for environmental stimuli, deciding which are the most relevant stimuli and thus placing a priority on them by way of concentration of mental activity on the objective , for more profound processing in the conscience. At the same time, attention is understood to be the mechanism which controls and regulates cognitive processes; from learning by conditioning to complex reasoning.

One can speak of different types of attention, the most basic being (a) selective attention, in which the body focuses perception on one sole source of information, ignoring other stimuli, (b) divided attention, consisting of the processes which an individual puts into operation in order to pay simultaneous attention to several demands in the environment presented to him or her all at once or on given tasks, distributing attention resources among the activities or stimuli and (c) sustained attention, which means the persistence of attention in time to concentrate on one task.

Attention is influenced by internal and external states. Among the former are emotional activation and arousal, the state of the body, the attitude of interest towards the configuration of the stimulus, the expectations of effectiveness and outcomes which the individual has about an activity and social suggestion. The latter may be briefly summarized as the power of the stimulus, a change in the field of perception (novelty), size, movement, contrast and organization.

Example: PHMs make it possible to gather information about what stimuli our user should pay attention to selectively, and whether or not the user pays attention to the part of the scene that is relevant. It also allows us to evaluate whether the individual pays attention to one or more areas in the virtual environment (selective vs. divided attention), or whether he or she is able to change the focus of attention in accordance with needs in the task. It also provides us with information about the user’s need to keep attention focused during a task while inside of the virtual environment. PHMs allow us to perform evaluation by comparing what users pay attention to inside the virtual environment and determine whether internal states (such as arousal) play a role in the attention process.

PHMs are a tool used to provide information on the initial evaluation prior to the intervention. The data and color maps obtained complement the information on subjective self-reported measurements (such as Subjective Anxiety Units) and the physiological measurements (e.g., skin conductance level).

PHMs also provide us with basal information on the user’s behavior when interacting with the virtual environment. The most important behavioral measurements with which work can be performed are the orientation reaction, purposive behavior, exploratory behavior, appetitive, avoidance and fight-flight behaviors and the attention process (selective, divided and sustained attention). For further information about these variables, please refer back to Point 3 of this document: Basic concepts of behavior for clinical practice with heat maps.

Remember that the results of the initial evaluation provide highly relevant therapeutic information for analyzing and putting to use the patient’s initial state, and to establish hypotheses and plan the intervention.

During the intervention, PHMs are also a behavioral measurement which complements subjective self-reported measurements and physiological measurements, thus providing the required information on the triple response channel (behavior, physiology and cognition).

During the session, you can put to use the change in certain variables from the beginning to the end of the session. For example, in terms of exploratory behavior, you can assess whether the user has performed exploratory behavior when the environment first begins, whether the user remained still at the beginning and then explored more as anxiety decreased, etc. , such as those involving attention, and monitor change between tests: was the patient’s attention more divided during the exercise at the beginning of the sessions and then gradually focused with repetition of the task? You may establish objectives and therapeutic hypotheses, and compare them using the information provided by the PHMs.

Another way to use these behavioral measures during the intervention is to compare PHMs between sessions. If, for instance, the patient has performed one single therapeutic task (exposure to an environment to work on anxiety, attention training through mindfulness, etc.) in different sessions, PHMs can be very helpful for monitoring change during that training. Remember that you can gain access to all of the information on your patients and all of the contents created during the sessions in the Reports section of the Psious.pro side menu.

Last of all, we would like to point out that another useful way to monitor therapeutic change is to make comparisons in terms of therapeutic goals, between the evaluation session and the last session with intervention, and between the evaluation session and some of the tracking we eventually perform on our user: How was the user’s interaction with the environment during a specific mindfulness exercise on the first day of use, and how was it during the last session of the therapeutic process? Were the attention skills acquired and measured at the last therapy session maintained six months after that session was completed? If you change the therapeutic goal, which was attention training in the case of the example, for any other, such as handling anxiety, pain management, etc.

Psious heatmaps (PHMs) are yet another tool within the Psious.pro ecosystem. The main purpose of PHMs is to provide information on the patient’s behavior when interacting with a virtual environment. This information is a systematic measurement put to practical use (area and time of interaction by the patient with the virtual scene) regarding the patient’s non-verbal behavior over a time period specified by the therapist, whether in a full session with different environments and scenes , one specific scene, or even a part of one scene or what happened right after executing a specific event.

Within Psious.pro, PHMs are yet another measurement which, coupled with the information that can be collected from the patient through self-reporting (Subjective Anxiety Units, Attention, Pain, Craving, etc.) and objectively (Skin Conductance Level), make it possible to perform overall evaluation and monitoring of the patient while he or she is situated within a virtual environment.

It uses the Psious.pro control center timeline.to seek clinically relevant moments whether for evaluation or interventions, and it uses the PHM to ascertain how the patient was oriented visually at that time, and whether the patient spent much or little time that way.

Be imaginative. Our recommendations are just that: a way to help guide you and inspire you. Surely you can come up with many therapeutic ways to use PHMs.

Last of all, remember that it is very important to use the Psious.pro tools at all times with therapeutic goals and logic in mind. That way you will be able to make the most of this technology and offer your patients the best of these therapies.

Carry out a clinical assessment of your patient’s condition before starting the intervention. Use the data obtained in the evaluation to establish therapeutic goals and choose the most appropriate intervention strategies.

Use Psious tools to optimize the intervention and adjust them to the patient’s needs. Evaluate, periodically, the therapeutic process and, if necessary, adjust it. Somatic disorders are of great heterogeneity and variability: always use digital tools as a system to improve the intervention and not as a technique in itself.

“All the information contained in this section is for guidance only. Psious environments are therapeutic tools that must be used by the healthcare professional within an evaluation and intervention process designed according to the characteristics and needs of the user.

Also remember that you have the General Clinical Guide in which you have more information on how to adapt psychological intervention techniques (exposure, systematic desensitization, cognitive restructuring, chip economy…) to Psious environments.”

In this section we propose different strategies and tools on how to anxiety, sadness, physical activity and sports performance training:

Considering the evaluation objectives, we will enumerate some of the tools that can be useful to obtain relevant information about the characteristics of your user. Remember that good objectives definitions, patient characterization and planification of the intervention are important for therapeutic efficiency and effectiveness just like the user satisfaction. In the bibliography you will find articles where you can revise the characteristics of the proposed tools.

Exercise & Sports performance training is a new therapeutic area that includes different environments for physical and sporting activity and some techniques for improvement of sport performance.

First, research has demonstrated, quantitative and qualitative, the efficacy of exercise in clinical samples. The meta-analysis of 11 treatment outcome studies of individuals with depression yielded a very large combined effect size for the advantage of exercise over control conditions (Stathopoulou, G., et al., 2006). Exercise seems to be effective as an adjunctive treatment for anxiety disorders but it is less effective compared with antidepressant treatment. Both aerobic and non-aerobic exercise seems to reduce anxiety symptoms.

There have been a few hypothesised mechanisms of anxiety reduction following exercise; enhanced self-efficacy, experiences of mastery, distraction from anxiety-provoking stimuli, a method of exposure therapy, neurotransmitter changes, peptide changes and changes of self-concept have been proposed( Martinsen EW, et al. 1989, Broocks A, et al. 1998, Strohle A. 2009, Jayakody, K.et al., 2014). Based on these findings, we encourage healthcare professionals to consider the role of adjunctive exercise interventions in their clinical practice.

On the other hand, physiological (activation levels, respiratory and muscle tension management…) and cognitive process (attention, concentration, thought management…) can be evaluated and trained to improve sports performance (Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E., 2006 & 2019; Mardon, N., et al, 2016; Moen et al., 2016; Ducrocq, E., et al. 2018).

Virtual Reality (VR) has been shown to improve adherence to exercise, be effective in training race pacing strategies, enhance effort, improve mood and enjoyment, and increase cognitive functioning when compared to control conditions (Neumann, D. L. , 2016).

A recent review indicates that VR can be a promising adjunct to existing real-world training and participation in sport. A VR-based system for training and participation has several advantages such as enabling athletes to train regardless of weather conditions, providing a means to compete with others in a different geographic location, and allowing precise and replicable control over features of the virtual environment (Neumann, D. L. et al. , 2018, Gardner, F. L., & Moore, Z. E., 2019).

Psious’ “Exercise & Sports performance training” tools were created to help healthcare professionals with the management of anxiety and mood related symptoms and with the training and improvement of sport performance. These tools can help the patient by means of evidence-based techniques: Breathing Techniques, Progressive Muscular Relaxation, Imaginary, Body Scan & Mindfulness.

Mood-related environments are tools that can help your client cope with their different moods, especially if you use the data obtained during your work with the patient to make the virtual experience most relevant to them.

To increase the sense of immersion in Virtual Reality, you can include comments, questions or ideas in the session so the experience will seem more realistic and relevant to your patient.

“All the information contained in this section is for guidance only. Psious environments are therapy supporting tools that must be used by the healthcare professional within an evaluation and intervention process designed according to the characteristics and needs of the user.

Also remember that you have the General Clinical Guide in which you have more information on how to adapt psychological intervention techniques (exposure, systematic desensitization, cognitive restructuring, chip economy…) to Psious environments.”

In this section we propose different strategies and tools on how to evaluate mood.

Considering the evaluation objectives, we will enumerate some of the tools that can be useful to obtain relevant information about the characteristics of your user. Remember that good objectives definitions, patient characterization and planification of the intervention are important for therapeutic efficiency and effectiveness just like the user satisfaction. In the bibliography you will find articles where you can revise the characteristics of the proposed tools.

Depressive disorders include a group of mood disorders, for example: disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, major depressive disorder (including major depressive episode), persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia)… What differs among them are issues of duration, timing, or presumed etiology. The common feature of all of these disorders is the presence of sad, empty, or irritable mood, accompanied by somatic and co changes that significantly affect the individual’s capacity to function (adapted from APA, 2013).

Depression affects an estimated one in 15 adults (6.7%) in any given year. And one in six people (16.6%) will experience depression at some time in their life (Kessler, RC, et al. 2005).

The mood in a major depressive episode is often described by the person as depressed, sad, hopeless, or discouraged. Some individuals may complain of feeling bored, having no feelings, or feeling anxious. Other individuals may emphasize somatic complaints (e.g., bodily aches and pains) rather than reporting feelings of sadness. Many individuals report or exhibit increased irritability. In children and adolescents, an irritable or cranky mood may develop rather than a sad or dejected mood. This presentation should be differentiated from a pattern of irritability when frustrated. (adapted from APA, 2013).

Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) has a probably effective evidence-base in the treatment of major depressive disorder, the effects are large when the control condition is waiting list, but small to moderate when it is care-as-usual or pill placebo. of the small number of high-quality trials, these effects are still uncertain and should be considered with caution (Cuijpers, P. et al., 2016).

There is however a striking dearth of VR interventions for depression (Freeman, D., et al., 2017, Linder et al., 2019). This manual describes different ways of translating traditional CBT techniques for depression into the VR modality, as well as how to make use of the inherent capabilities of VR-unique experiences to improve depression symptoms. Psious’ “Depression” therapeutic area tools were grouped to help healthcare professionals on mood assessment and treatment, especially for major depressive disorder.

This tools can help for low-intensity depression symptomatology treatment using CBT evidence-based techniques: Behavioral Activation, Social Skills Training and Physical Activity, Cognitive Restructuring and Positive Affect Training (Linder et al, 2019, Craske et al., 2019).